Freddy Greene: Street Genie of Franklinton

Legendary Franklinton native and saxophonist, Freddy Greene

"I was born in a Juke joint," Freddy Greene, locally known as Street Genie, he says with the grin of a storyteller settling into a well-worn tale.

The place, called the Chicken Shack, was a small log cabin just outside of Franklinton that, despite its size, served as a thriving community outpost. In the evenings you could always find a good time with singing, dancing, and more than anything else, a constant stream of music. When it closed in 1958, Freddy's parents moved right in. For Freddy, being born where music once lived and breathed meant something deeper than just geography.

The musical lineage runs even deeper than that old juke joint. Years later, at his aunt's funeral, Freddy discovered a photograph in the family album that would reshape his understanding of his own musical DNA. There, among the family pictures, was a photo of W.C. Handy—the Father of the Blues himself.

"I went to the oldest man in the family and I said, 'What is this picture doing in our family album?'" Freddy recalls. "He told me, 'He and your great uncle Ali were good friends up there in New York. I remember him coming on down here, he was hanging out with everybody and playing the piano in that Chicken Shack you were born in.'"

He soon found out there were other notable musicians that made their way through the Chicken Shack, like Fats Weller, the famous jazz pianist. The revelation that these music legends had once played piano in the building where Freddy drew his first breath feels less like coincidence and more like destiny. It's the kind of story that makes you believe in the power of place, in the way music can linger in walls and floorboards, waiting for the right person to come along and carry it forward.

But when asked who inspired him the most in his musical journey, Freddy immediately says “my mother, Flora Mae” and his eyes light up with the kind of warmth reserved for sacred memories. After being encouraged to nurture his musical talent, he found himself playing the piano for his grandmother at 5. Next was the trombone at 10, the bass guitar at 12, and then, finally, at 17, Freddy found the saxophone. It would soon become his voice, his companion, and eventually, his passport to stages from street corners to the Apollo Theater.

Freddy first started playing his instrument in the streets in Chapel Hill, Durham, and Raleigh around ‘77, while he was going to St. Augustine’s. Then, when he went to North Carolina Central University, he studied under legends like the Moon Brothers along with legendary jazz trumpet pioneer Donald Byrd who taught him the most important lesson of all with a single word: "Practice."

"He instilled in me a state of mind," Freddy says. "I would practice eight, ten hours a day. I would practice walking to class with my horn. When I was back home, I walked down the street going to the store, practicing my horn. I guess some folks thought I lost my mind. But I wasn't losing my mind. I was losing myself to find myself."

Eventually Freddy found himself practicing eight to ten hours a day in a shack where snow came through the roof and rain found every crack, he was deep in what he calls "dropping out of society" to find his sound. Around 1983, his cousin in Washington, DC, Kenney Greene, suggested that Freddy move there to find better opportunities. He agreed, and then often spent his afternoons playing as a street musician in Georgetown.

Then, one day, a man walked up to where Freddy was playing and dropped two slips of paper into his open hat. When Freddy picked them up, he discovered two airline tickets to New York. Freddy knew this was a once in a lifetime opportunity, so he was going to make the most of it.

"Almost like fate," Freddy says. "I'm not only going to be flying on an airplane for the first time, I'm going to the Apollo."

And so, after making call after call he somehow managed to get a spot performing one night. Walking on the stage, he was nervous. But, once the lights went on and he lifted his saxophone, he knew he was where he was meant to be. He won fifth place among all those wonderful performers, and the experience taught him something that would shape his entire approach to performance: the power of connecting directly with people. "You win by people clapping," he explains, and that lesson carried over to his true love—street performance.

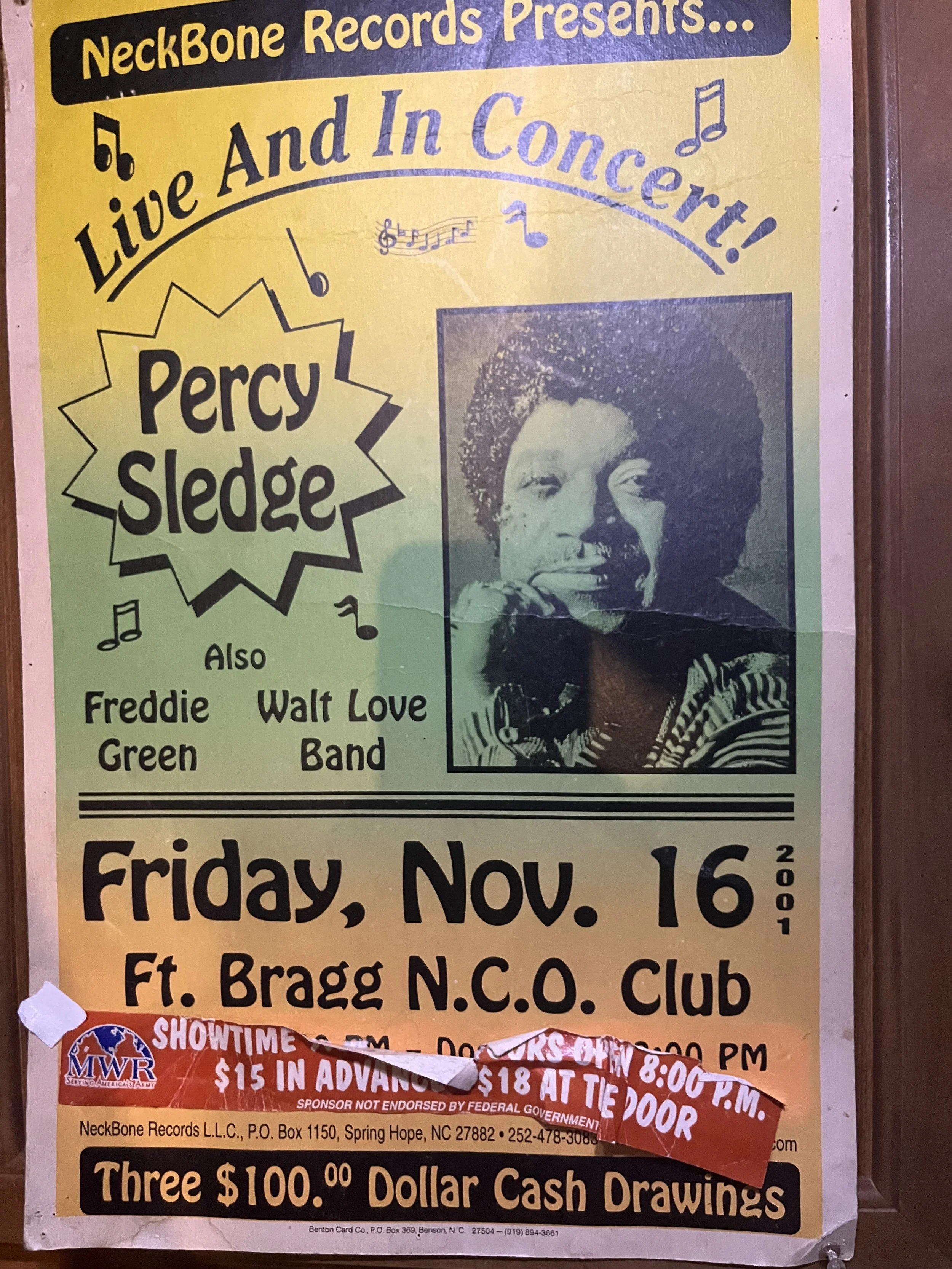

A venue poster proudly lists Freddy alongside legendary singer Percy Sledge.

He's heard it all, from "That is so beautiful, you made my day" to "What's that you’re playing, man? Get a job." But rather than discourage him, the full spectrum of human response became part of his artistry. "I learned how to say how I feel without saying it, and how to connect with people."

Stories flow from Freddy like music itself—meeting Miles Davis backstage (sort of), tricking his way into the office of a CBS Records executive, playing with legends like Shirley Caesar, the Queen of Gospel, who he still plays for today, touring with Percy Sledge, and traveling with Reverend Dr. William Barber. Each tale carries the same thread: a man who understands that music is about connection, about finding the human heart in every note.

Today, Freddy continues to carry forward the musical legacy that began in that old Chicken Shack in Franklinton. Whether he's playing on a street corner as the longest-running street musician in Raleigh, traveling with gospel royalty, or sharing his stories, he embodies the truth his mother's tale always contained: that music has the power to rescue, to connect, to heal.

"Make your instrument part of who you are," he advises young musicians. "It gets in your spirit, in your soul, it gets to be a part of who you are."

In Freddy Greene's hands, the saxophone isn't just an instrument. It's a bridge between the juke joint where he was born and every street corner, concert hall, and human heart his music touches. It's the sound of Franklinton, the voice of the Chicken Shack, and the continuing story of a man who learned early that sometimes the most profound connections happen not on grand stages, but in the simple, honest space between one person and another, with nothing but music to carry the truth between them.

Over his career, Freddy has recorded eight full CDs and three singles. You can find Freddy’s music on Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon, and social media. His most recent album, One Hour At The Altar, was just released and the album cover features a painting created by the musician himself.

To book Freddy for a performance, visit his website at https://freddygreene.com/,

email him at fgreenesax@yahoo.com, or give him call him at 919-692-5487.